What is Urban Morphology for Refugees?

“Urban morphology is the study of the city as human habitat…Urban morphologists focuses on the tangible results of social and economic forces: they study the outcomes of ideas and intentions as they take shape on the ground and mould our cities. Buildings, gardens, streets, parks, and monuments are among the main elements of morphological analysis. 1”

For refugees, urban morphology is often characterized by various conditions of impermanence and uncertainty. Urban morphology for refugees is a morphology of indeterminacy that begins with the moment of leaving home, through travel to a host country, during the time in a host country until asylum is granted, during integration and rebuilding a life in the host community, and, when possible for or desired by the refugees, the time of return and rebuilding in the home community. Because the types of urban form encountered vary widely in each stage of these refugee experiences, we here distinguish four provisional categories of urban morphology important in contemporary refugee situations.

In addition to these four broad categories, in many respects, urban morphology for refugees is a morphology of networks and flows in constant flux as much as it is about more traditional aspects of urban form such as city blocks, neighborhoods and streets. The particular spatial and social flows and flux for refugees is made possible by digital information technologies that allow for communication across spatial and political borders; therefore, it is essential to include digital technologies in the study of urban morphology for refugees.

The Journey from Home to Host Country

From leaving home to arriving in a new housing country, refugees travel through numerous towns, cities, regions and countries; along the way they are sheltered temporarily in numerous formal and informal temporary facilities. Refugees, when asked, remember town and city names but hardly neighborhoods and other larger urban morphological elements. They remember very well particular buildings and smaller places where they stayed (therefore see section on Building Typology.

Arrival and Interim Shelter in Host Country

Upon arrival to a host country, refugees are often sheltered at temporary ‘processing’ facilities. Days, weeks and sometimes months later, refugees are transferred to longer-term interim housing while asylum or migration applications are processed. These interim facilities include temporary tent camps erected either within or outside existing towns and cities, as well as repurposed spaces, also either within or outside existing towns and cities. The scale and duration of these camps varies greatly, from relatively small temporary tent camps of a few hundred that are dismantled after a year (Essen, Germany) to huge camps (as whole cities) are being built for refugees to accommodate and control huge numbers of people. Refugee camps may be the most clear category of a refugee urban pattern.

Integration and Permanent Shelter in Host Country

“Permanent” housing and other refugee spaces are often not available in host countries for months or years, or even decades. However, older and run-down neighborhoods are sometimes used by refugees and migrants, so that they can live together in familiar environments, such as in the neighborhood of Molenbeek in Bruxelles and in the neighborhood of Marxloh in the city of Duisburg, Germany.

Return and Rebuilding in Home Country

The fourth type of urban morphology for refugees is that of return and potentially rebuilding in the home community, when desired and possible.

Refugee Camps

Our research investigates the particularities of how urban morphology is both shaped by and influences refugee movements in Europe and elsewhere. In our first contribution we investigate the six largest refugee camps in the world, several of them with populations of several hundred thousand people. We also present a short article that discusses the controversial nature of neighborhoods for refugees in European countries because of their potential for ‘parallel cultures,’ ‘multi culture,’ and concerns about ghettoization of refugee communities. The article is called ‘Mosaic of subcultures.’

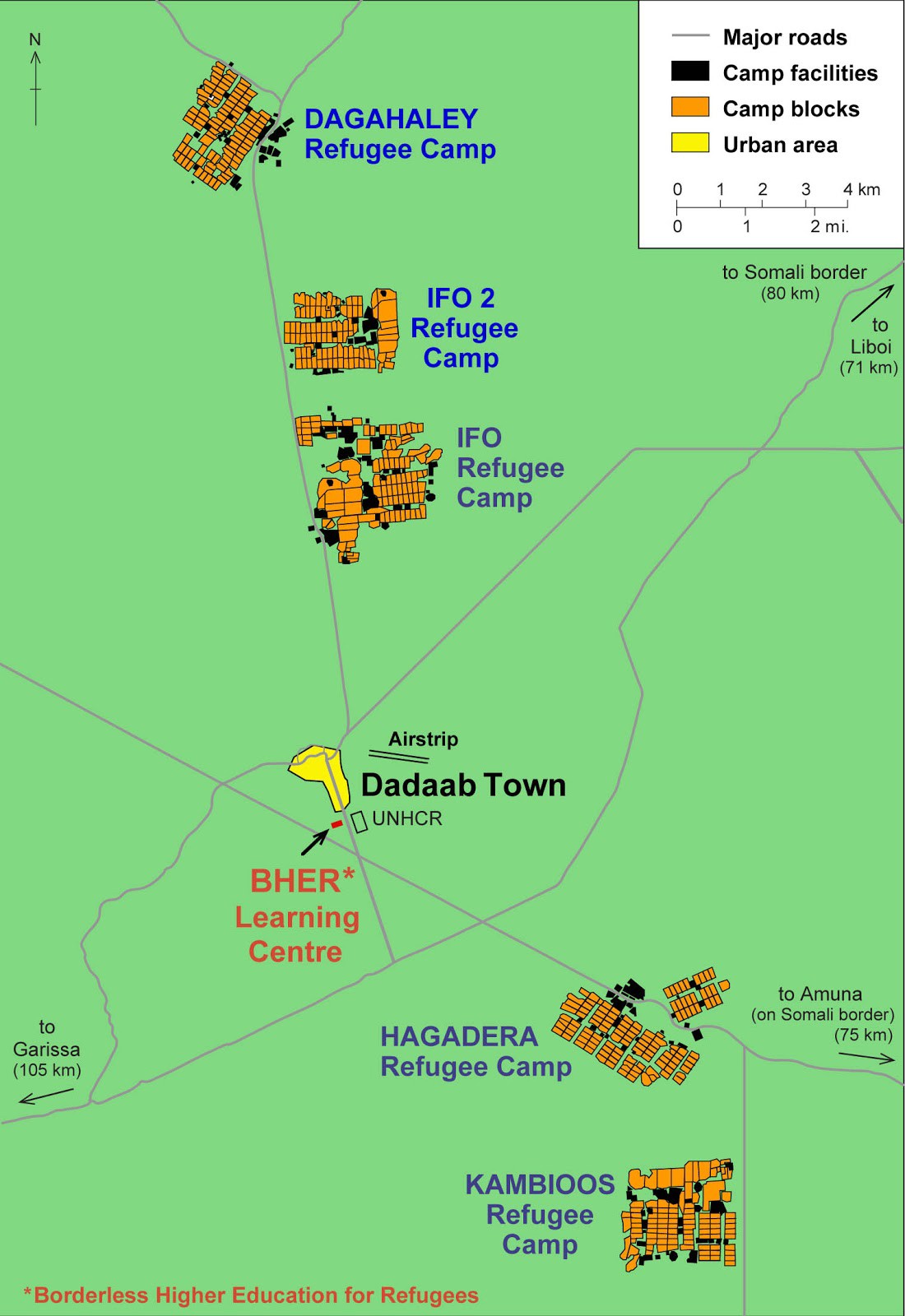

Kenya – Dadaab

The Dadaab refugee camp is located in eastern Kenya (image 1), 71 km from the Somali border and 107 km away from the nearest city of Garissa2. The region is semiarid desert with a yearly rainfall of 338mm and an average temperature of 28.6℃. Most of the refugees are victims of the civil wars going on in Somalia and have been coming to the camp for 24 years. The refugees work for the aid organizations, maintaining the camp but not contributing to the economy of Kenya. The half million person camp is split into 5 districts, each with blocks of housing, surrounding a central node of community buildings3.

Image 1: Dadaab Location in Kenya

http://www.bher.org/about-bher/dadaab-camps/

These nodes enclose the primary schools, hospitals, markets, religious centers, community centers, and food and water distribution points.

The refugees reside in reed huts, covered with mud, paper, or plastic sheeting provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). There are typically four or more people per hut, with minimal furniture4.

Nepal – Beldangi

The two Beldangi camps of South Eastern Nepal consist of ethnic Nepali refugees from Bhutan. The camps have the highest rate of third country acceptance in the world, bringing the number of Bhutanese refugees in the country from 106,000 in 7 refugee camps in the 1990s to 3 as of 20155. The camps are located in the tropical region of South Eastern Nepal set into a bamboo forest adjacent to rice farms and 6 kilometers from the Nepalese town of Damak. The two camps are separated by a half kilometer of bamboo forest.

The larger of the two camps is divided by two intersecting main roads, and most public buildings such as the church, market, community center, school, and office buildings are located at the junction of these roads. Public buildings are built of bamboo, corrugated metal sheets or concrete. Residences are spread out around this central node in lines spaced by bamboo trees6.

The camps are adjacent to a Nepalese highway, and the close proximity to Nepalese people allow trade to happen in the camps. Since many refugees have been successfully transferred to third countries, these refugees have been sending back money for friends and family still at the camps. Those at the camps are using this money to set up businesses such as phone charging stations, beauty salons, tailors, or fast food restaurants. However, there is no legal employment for the refugees, and much of their time is spent idle or constructing and repairing structures at the camps7.

The camps appear to be more like villages than refugee camps, with most structures being made of bamboo using the natural resources of the surrounding jungle, and not the typical UNHCR supplied tents. These bamboo huts are sided with newspaper and often painted. Water taps are located near housing units, and cooking is done with cooking fires on the ground inside the huts8.

Jordan – Al Zaatari

There are 80,000 Syrian refugees at the camp as of December 2015. The camp covers 5.3 square kilometers and is 15 kilometers from the Syrian border to the north.The camp is located in an arid desert climate near multiple small villages and is 12km away from Al Mafraq, a large town with an airport and university9.

The camp is organized in a grid of streets, with housing in city block like units. The hospitals, schools, markets, and community centers are lined along the main roads that cross the camp. The Zaatari market consists of an estimated 3,000 refugee operated shops and businesses. These businesses and household consumption commodities trade, and NGO short term cashforwork activities at the camp have led to 60% of the working age refugee population to earn some form of income10.

UNHCR supplied portable box housing and tent units make up the majority of the housing. The tent is typically separated into two rooms, a sleeping room and a living room11. The households are connected to a camp wide electricity grid and are able to access electricity for 11 hours per day. A solar power plant is under construction that should be operational by the end of 2016 to cover the camp’s energy costs. Waste is treated at a nearby wastewater treatment plant, collected by sewage trucks. Recycling projects involving the refugees lower the camp’s waste12.

Turkey – Kilis Oncupinar

The refugee camp of Kilis Oncupinar is located in Southern Turkey less than a kilometer from the border with Syria. The camp houses 14,000 Syrians in 2053 identical containers. The camp is located in an arid desert environment and is 8 kilometers from the town of Kilis to the north. The camp is run by the Turkish government and is one of six container camps which try to provide a higher quality of living than in standard refugee camps through better quality housing and food, access to electricity and highly cleaned and maintained facilities13.

The camp is organized in a linear formation along the checkpoint at the Turkish border. The markets, school, hospital and community buildings are located at the center of the camp with housing spread out to the north, west, and south14.

France – Calais

Calais is a French port town of 126,000 people as of 2010. It is set at the narrowest point of the English Channel, 34 kilometers from Dover, England. The climate is temperate oceanic, with moderate winters. Refugees wait in Calais for the opportunity to cross the border into the UK by being smuggled on a truck or ferry.

The Calais “Jungle” has little organization and consists of scattered tents in multiple forested areas around and in Calais. For most of the jungle there are no sanitary facilities, and food is supplied by charity soup kitchens15.

The camps are home to mixture of refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants. Migrants largely are coming from the Middle East and Africa. The camps are set on unoccupied land in and around Calais, and move as the camps are shut down by authorities. The camps were originally formed in 1999. One of the current sites is located on a landfill and is home to 1000 of the 6000 people at the camps as of November 201516.

Tents in the camps are pade of plastic sheets and are often not large enough to stand in. As of January 2016, 125 container housing units were opened to increase sanitary conditions but because of registration requirements, many people fear they will not be able to get to the UK if they register for housing, so many of the containers are vacant17.

Ecuador – Ibarra

Columbia has the world’s highest rate of people displaced by violence. Many of these refugees travel to Ecuador, which now has the highest number of refugees in Latin America.17 An estimated 135,000 people have crossed into Ecuador as of last 2014 according to UNHCR.17 Many of these refugees are living in the border regions of Carchi and Imbabura at the north border with Colombia18.

The approach to refugees in Ecuador is social and economic integration as opposed to refugee camps. These refugees can legally work if they are granted a refugee visa, and all people are granted education and healthcare without requiring a refugee visa. Only 30% of applicants are officially recognized as refugees and gain the visa, and those who get rejected stay in the country. The UNHCR is supporting the integration by leading projects such as upgrading school infrastructure, implementing family commercial farms in rural areas, training refugees in business management and advising partner non profit agencies in the country19.

- Moudon, Anne Vernez. “Urban Morphology as an Emerging Interdisciplinary Field.” Urban Morphology (1997), 1, 3-10 ↩

- http://lltd.educ.ubc.ca/media/dadaab-camps/ ↩

- http://www.aquila-style.com/focus-points/global-snapshots/lure-of-high-risk-riches-too-strong-for-somalia-refugees/101375/ ↩

- https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/may/20/dadaab-refugee-camp-kenya-repatriation-somalia ↩

- https://www.thestar.com/news/world/2015/09/21/worlds-large-refugee-camp-in-kenya-could-be-the-future.html ↩

- http://kenan.ethics.duke.edu/uprooted-rerouted/introductions/nepal.html ↩

- ibid. ↩

- ibid. ↩

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/jordan/11782770/What-is-life-like-inside-the-largest-Syrian-refugee-camp-Zaatari-in-Jordan.html ↩

- http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/05/09/world/middleeast/zaatari.html ↩

- ibid. ↩

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/jordan/11782770/What-is-life-like-inside-the-largest-Syrian-refugee-camp-Zaatari-in-Jordan.html ↩

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/11199951/The-terrible-danger-facing-Syrias-refugees.html ↩

- http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/magazine/how-to-build-a-perfect-refugee-camp.html ↩

- http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-calais-idUSKCN0UP23R20160111 ↩

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/06/at-night-its-like-a-horror-movie-inside-calaiss-official-shanty-town ↩

- http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21677987-france-has-less-and-less-influence-eu-and-fears-use-what-it-still-has-dispensable ↩

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6132216.stm ↩

- http://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/RefugiadosAmericas/Ecuador/2011/UNHCRs_work_in_Imbabura_and_Carchi_Aug2011.pdf?view=1 ↩